Community Support Officer, Community Justice Glasgow

DID YOU KNOW?

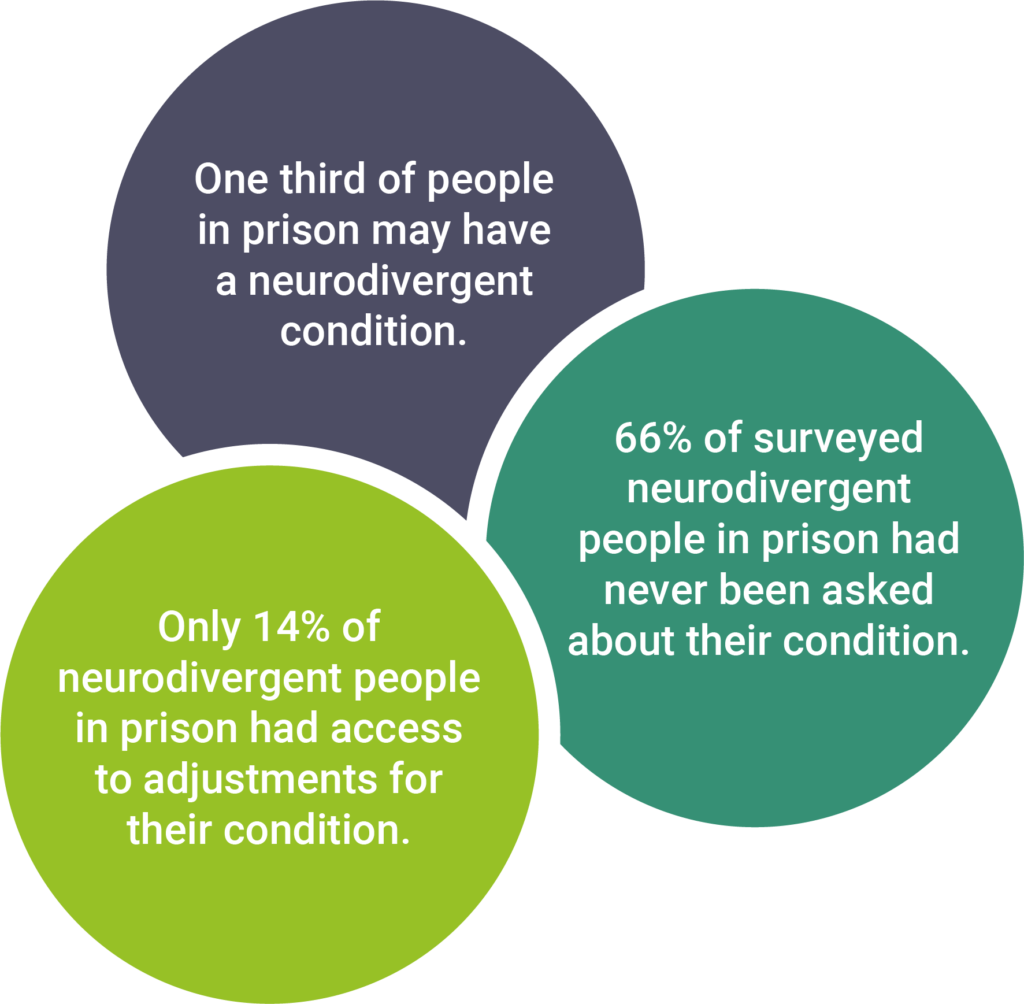

1 in 3 people in the prison and as many as half the people in the criminal justice system overall have a neurodivergent condition.

71% of neurodivergent men and 47% of neurodivergent women in prison had been labelled with negative terms such as ‘bad, naughty, or thick’ at school.

66% of service users surveyed by User Voice had never been asked about having a neurodiverse condition during their journey through the justice system.

Currently, there is no reliable data on the number of neurodivergent people in contact with the justice system.

Neurodivergence refers to the way in which an individual’s brain functions differently from what can be considered “neurotypical”. This term is often used to describe people who have conditions such as Autism, Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), Dyslexia, and other cognitive or developmental differences. The term “neurodiversity” highlights that these variations are a natural part of human diversity, rather than disorders that need to be “fixed”. Around 15% of people are estimated to have a neurodivergent condition, however this rises to an estimated 1 in 3 people in prison and as many as half of the people in the criminal justice system overall. The criminal justice system, like many systems in our society, is an example of neurotypical service design because it is structured around assumptions of cognitive and behavioural responses that align with neurotypical norms. As a result, neurodivergent people and those with learning disabilities may struggle to navigate the system effectively, facing disproportionate challenges and outcomes, which can lead to reoffending.

Crisis Points: What drives neurodivergent people into the criminal justice system? – For many neurodivergent people and those with learning disabilities, their trajectory into the criminal justice system begins in school. A 2023 study by User Voice found that 71% of neurodivergent men and 47% of neurodivergent women in prison had been labelled with negative terms such as ‘bad, naughty, or thick’ at school. Those labels were often based on behaviours such as hyperactivity, which is consistent with an ADHD diagnosis, or the learning challenges experienced by people with dyslexia. Many reported that these negative labels became a self-fulfilling prophecy, influencing their behaviour throughout life and perpetuating a cycle of marginalisation.

The same study found that 30% of male and 24% of female service users had been in care, while 47% of male and 76% of female service users had experienced abuse early in life. People involved in the criminal justice system are more likely to have had adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), and care leavers, who make up only 1% of the UK population, are estimated to represent 25% of the prison population.

For young people who receive a diagnosis later in childhood or adolescence, the lack of support available can be even more pronounced. A 2022 study found that 66% of autistic young people received a late diagnosis, and that this cohort reported “milder problems in early childhood, but then showed a steeper growth in their difficulties, such that by 14 years they had higher levels of emotional, behavioural and social difficulties”. Without early diagnosis, these young people can miss out on critical support and interventions resulting in unmet needs which cause behavioural issues. These behaviours can be misinterpreted as defiance or aggression, increasing the likelihood of repeated negative interactions with the criminal justice system in the future.

The outcomes for neurodivergent young people can also be intensified by stigma from parents, caregivers, and schools, which can continue throughout their lives and interactions with support systems. The connections between neurodivergent stigma and ACEs create a perfect storm, making these people more vulnerable to becoming involved in offending behaviour.

Engagements with the Police can also prove challenging. The Police can be treated as a de facto mental health emergency service in times of crisis, and while Police services across the country have been taking positive steps to meet this need, the support provided may not always be appropriate. For instance, in the case of autistic people, meltdowns can easily be misinterpreted as aggression which can trigger a negative interaction with Police and other services.

Entering the Cycle: How do neurodivergent people experience the criminal justice system? – Navigating the criminal justice system is a daunting experience for anyone, but for neurodivergent people it can present specific and unique difficulties. The system, often designed with neurotypical expectations in mind, can be particularly unforgiving for those whose neurological differences affect their behaviour, communication, and decision-making processes.

The complexity of the criminal justice system poses significant difficulties for neurodivergent individuals. The system’s rigid structures and procedures, coupled with the expectation of understanding and adhering to specific norms, can be overwhelming. This is particularly true for those with conditions like autism or dyslexia, who may struggle with processing complex information, understanding legal jargon, or managing the high-stress environments often associated with the justice system. These challenges often leave neurodivergent individuals at a disadvantage, leading to misunderstandings and, at times, mistreatment within the system.

Repeat offending itself can be an indication of a neurological condition. For example, impulsivity – a common trait in people with ADHD – can result in repeated offenses, while difficulties with executive functioning – often seen in both autism and ADHD – can cause a person to fail to grasp the consequences of their actions. In some cases, repeat offending might indicate a person’s difficulty in moderating their behaviour. This does not excuse neurodivergent individuals from responsibility for their actions, but it does suggest that more positive interventions could be available to help break the cycle of repeat offending, especially if these patterns occur without a formal diagnosis. 66% of service users surveyed by User Voice had never been asked about having a neurodiverse condition during their journey through the justice system. This oversight represents a missed opportunity to engage individuals in interventions that could reduce their risk of reoffending.

Even when undergoing treatment or receiving support for their conditions, some neurodiverse people struggled to have their needs fully met. Of the 104 service users interviewed by User Voice, only 14% had adjustments made for them around their condition, which may include access to noise cancelling headphones, access to a gym, or literacy support. The lack of such accommodations can have serious consequences. For example, autistic meltdowns—intense emotional or sensory responses triggered by overstimulation – can easily be misinterpreted as aggression, leading to escalated responses from prison staff. Additionally, for those with ADHD, many reported that the only support they received was medication, which was often inconsistent due to some ADHD medications being controlled substances not permitted within the prison system.

Breaking the Cycle: What do neurodivergent people need? – It is well understood that neurodivergent people benefit from having tailored adjustments to meet their needs in various services, from education to housing. It stands to reason that this would also extend to the criminal justice system. Since neurodivergent responses to stress can be concurrent with offending behaviour, minimising the stress they experience during incarceration can help them to avoid the trap of reoffending. One approach to this is viewing the entry point into justice services as an opportunity to screen for potentially undiagnosed neurodivergence, allowing for the diversion of individuals with additional support needs to alternatives to prosecution where appropriate. Currently, there is no reliable data on the number of neurodivergent people in contact with the justice system. Collecting such data would not only be valuable for understanding the scope of the issue but also for identifying those who could benefit from assistance in navigating the justice system in a more accessible way. Often, community-based sentences are more effective at reducing reoffending than short-term prison sentences. These alternatives can also support neurodivergent individuals by helping them maintain their routines and access tailored support within the community.

For those for whom it is judged that a prison sentence is appropriate, a rights-based approach that acknowledges that people have specific needs may help them to avoid high-stress situations while incarcerated. Victimisation while in prison may be a driver of reoffending, and evidence suggests that autistic people, in particular, may be vulnerable to manipulation. Where single cells are available, these can be used to mitigate sensory overload and avoid negative interactions with peers. Autistic people also benefit from extremely clear, direct communication and may often prefer written communication, so prisons can meet this need by ensuring information is available in accessible formats. For people with ADHD, engaging in recreational activities can improve focus and provide positive outlets for energy. Activities such as chess or access to the gym can help these people cope with imprisonment more positively. People with specific learning difficulties can benefit from visual aids including simple guides to prison processes, tailored educational resources and legal advice, and access to learning tools such as audiobooks, dyslexia-friendly fonts, and visual schedules.

Most importantly, continued support upon release is crucial for neurodivergent individuals. The disruption caused by a prison sentence is always significant, but for a neurodivergent person, it can be especially challenging to achieve a positive outcome afterward. Neuroinclusive improvements to community care and referral pathways, which are accessible from the moment of release, can make a significant difference. Access to stable housing, healthcare, mental health support, and social integration provides a strong foundation for reducing reoffending.

The treatment of neurodiverse individuals within the justice system, as well as in other areas of life, is being addressed by the Scottish Government’s Learning Disabilities, Autism, and Neurodivergence Bill. At the time of writing this bill’s consultation deadline is closed; you can read about the consultation here.